In the month of December, with the moon shining through the leafless trees on the evening of December 5th, we began the night of the Feast of Saint Nicholas.

There is actually very little known about this saint who is revered in many countries. He was probably born in Patras (or Patara), some 500 km from Myra (Lycia in Asia Minor, currently Turkey). In the 4th century he was the Bishop of Myra, and on December 6th, sometime in the year 350, he died. As is often the case, the less information known about someone, the more legends that exist around them.

Examples include his concern for the plight of poverty-stricken children, the many miracles attributed to him and his alleged attendance at the Council of Nicaea. In 1087, his relics were taken to Bari, Italy, to protect them from the advance of Islam in the area. In the Italian port, the St Nicholas Basilica was built in his honor. St Nicholas’s fame as a protector of families, children and homes grew. He is also known as the patron saint of Amsterdam.

For several years, I have been going regularly to Bulgaria. The first time I visited the country I was surprised by what I saw, how ‘foreign’ the icons appeared to me, so different from the images I was accustomed to seeing. However, very soon their ‘otherness’ captivated me and I was taken by their unprecedented beauty. The more icons I saw – and there are very many of them – the more I wanted to discover about them.

In the Icon Museum of Tryavna there is a large collection of icons, and as I wandered around I quite literally ‘fell in love’ with the depictions of the Mother of God, Christ and other saints. The helpful curator of the museum explained the patience and dedication that had gone into the creation of these icons. She spoke about their function as ‘helpers when we are in need’, providing comfort and solace to the sick and the poor. It made my own attempts to paint icons pale by comparison.

The icons in the Alexander Nevsky Crypt Museum in the capital, Sofia, are equally impressive. There is never enough time to explore the immense collection housed in this most remarkable location.

If you compare Bulgarian icons with, for example, Greek or Russian images, of course, you can straight away see similarities as they were (and still are) painted according to ancient traditions. However, what strikes you immediately with Bulgarian icons is the use of color: they radiate a special brightness and feeling of joy. Especially the Mother of God is often depicted in dazzling colors, sometimes with a hint of a smile on her lips. The sumptuous clothing and unique backgrounds reveal a wealth of detailed ornamentation and embellishments. There are numerous floral motifs, highlighted with fine gold hatching.

The azure blue background which appears to blend seamlessly into turquoise, offers a contrast to the more traditional gold background of many icons and gives Bulgarian icons a distinctive atmosphere and appearance. Also, remarkably, a strikingly ‘sweet’ pink color is often used in Bulgarian icons, requiring you to reconsider and get used to a different way of viewing them. To a great extent, you can find this also in icons from Macedonia, not surprisingly as it is a close neighbor. There is also overlapping to be found in Greek and Romanian icons.

For the Bulgarian people, icons and frescoes have always been very important. In the past poverty often defined and dominated their lives. Under the Ottoman Empire, churches nearly disappeared and were, some literally, forced underground. It was decreed that a church building could not be higher than a rider on a horse. Therefore many old churches, among them the one in Arbanassi, are sunk half-way into the ground. If you were unaware of its presence, you could easily pass by without noticing it. As a result of this policy, icons in churches and private homes provided comfort and support to the Bulgarian people during this difficult time.

Following are some examples of Bulgarian icons of Saint Nicholas.

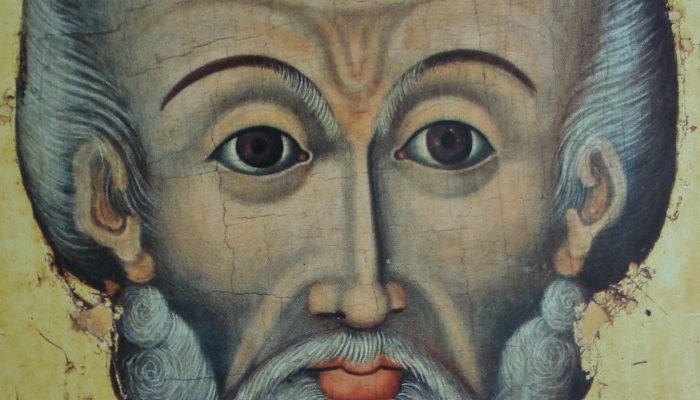

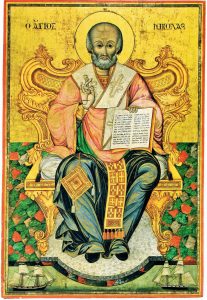

The enthroned Nicholas

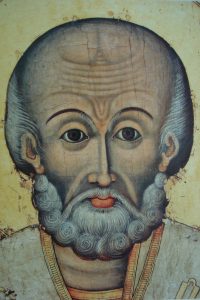

In my opinion, the face in this icon is considerably ‘different’ from others, yet the iconography is easily recognizable as Nicholas: the head with the broad, high forehead, the wrinkled face, the short grey hair and beard. What stand out are the folds on both sides of the nose as well as the typical creases above the nose bridge. These details illustrate the genius of Bulgarian icon painters. The heavy eyelids are characteristic of the way Bulgarians painters made St Nicholas and other icons of saints ‘their own’.

Let’s further examine this icon. It dates back to 1839 and is from the hand of Dimitar of Sozopol. This icon of Nicholas, sitting in an ornate ‘throne’ adorned with swirls and ornamentation, all in gold leaf, is gorgeous! However elaborate the image may be, it does not deflect from the central figure of the enthroned Nicholas. The elegance of the total representation with the splendid gesture of offering a blessing, is wonderfully portrayed. Of special note is the manner in which Nicholas holds the uncovered – also quite unusual as often it is presented with a cloth covering it – Book of Scriptures, not at the bottom as might be expected, but with the fingers of his left hand supporting the book at the top. And indeed, here we see the pale pink outer garment which together with the softness of the light stole, epitomise a trait – that of a gentle, kind man – attributed to Nicholas. A man of goodness; aware of those around him, concerned about the well-being of his fellow man.

The epigonation, (a Greek word translated literally as ‘on the knee’) which hangs from a strap originating on Nicholas’s left shoulder, rests on his right knee. The lozenge-shaped cloth is stiff to the feel and is a kind of badge of honor worn by Bishops during liturgical services. On the icon of St Nicholas, the epigonation is elaborately and richly embroidered and has three tassels hanging from its edges. It is said to symbolise the ‘spiritual sword’ of the Bishop, the Holy Ghost and the power of the angels.

Two different ships are depicted on the bottom of the icon signifying Nicholas’s importance as, among others, the patron saint of seafarers; the painter chose a unique and marvelous way of portraying this. The icon in its entirety testifies to the skill of the painter; everything is in balance; the composition as well as the coloring. The text on the icon is from a reading from the Gospel on the Feast Day of St. Nicholas in the Orthodox Church: Luke 6, 17-23: due to space constraints, it reads only until Verse 21, and then with the opening words, “At that time…”.

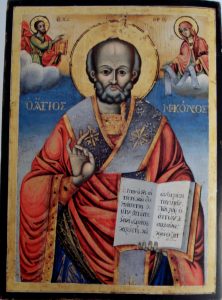

Nicholas the Wonderworker

The second Nicholas icon displays s a more sober style and, once again, the typical azure blue background can be seen. On the upper left side of the icon, Jesus Christ is presenting the scriptures to Nicholas and on the right, the Mother of God holds the omophorion, or bishop’s stole. Both figures appear in the clouds. Their offerings symbolise the restoration of his position as bishop, taken from him after an incident at the Council of Nicea in 325…yet another of the many stories surrounding this holy man, which gathered together would fill many books. Nicholas the Wonderworker is also from the hand of Dimitar of Sozopol in the year 1839.

The faces on Bulgarian icons often have a greyish undertone, with a bright, almost white, luminescence. The mouth is quite reddish with a strong lower lip, and the ears sometimes resemble graceful ornaments. Also in this image of Nicholas, there are furrows on either side of the nose and creases on the forehead above the bridge of the nose and eyebrows. The robe is not a soft, warm pink, but a stronger rose color, with dark shadowing in evidence in the very pronounced folds of the garment.

The omophorion or stole is beautifully decorated with gold flowers In place of the usual crosses; the star motif found on the shawl is reminiscent of the stars on the robe of Mary. The Holy Scripture rests on the saint’s hand on the underside of the book and is open to a passage from Matthew: “So I say to you: Ask and it shall be given you; seek, and you shall find; knock, and the door shall be opened unto you. For every one that asketh receiveth; and he that seeketh …” (Matthew 7, 7 = Luke 11, 9 to 10) If you give yourself over to this icon, you will most certainly be touched by its atmosphere and the representation of the holy man, Nicolas.

For icon painters who are interested in creating this image of St Nicolas the Wonderworker, we have included a drawing which you are free to copy and use.

The name of the iconographer of most Bulgarian icons is known and is indicated in the accompanying texts in museums and books. Icon painters signed a binding contract in which they ‘promised to do nothing wrong’, committed themselves to adhering to the traditional representations and colors, and attested to the fact that they were ‘worthy’ of the payment they received. The document was signed personally by hand.

In a book about the icons of Varna, there is an image to confirm this; it is a drawing of a hand next to a contract for icon painters from Tryavna, the cradle of Bulgarian icon painting. So literally, “From the hand of…”

Author: Marian van Delft