Among the activities surrounding the exhibition ‘Icons from Eikonikon’ the eponymous Dutch magazine devoted to Icons, which took place at the Stedelijk Museum in Vianen, the Netherlands, was a series of lectures. Peter van Dael, former professor of Art History at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam, currently author, teacher and priest gave a lecture on Images of Mary.

The talk took place in an appropriate setting as the museum extended the exposition to include the garden by recreating ‘The Garden of the Mother of God’, a nod to the sacred Mt Athos in Greece. The following is a summary of van Dael’s presentation.

The Adoration of the Blessed Virgin Mary

The veneration of saints began as early as the 2nd Century, a period of religious persecution and martyrdom, and was focused mainly on the martyrs. Devotion and rites were generally observed around their grave sites. In the case of Mary, her grave site was unknown at the time and therefore no relics, an important element of the worship of saints, existed. As a result, the recognition and glorification of Mary developed at a later time. In the 5th Century, the Third Ecumenical Council began a serious theological debate over the position and acceptable title of Mary in relation to the human and divine nature of Jesus. {ed. They eventually vaguely agreed upon Theotokos ” the Mother of God”, however this discussion would continue to spark in succeeding councils.} The 6th and 7th Centuries saw the introduction of a number of celebrations in Constantinople honoring Mary. These were embraced by Christians in many parts of the Western world.

Marian Relics

With the growing veneration of the Blessed Virgin came a renewed interest in discovering her tomb and an increasing demand for Marian relics. As historical research was mainly apocryphal and therefore provided no documentation or evidence for the actual site, speculation and conjecture were rife. Hearsay and anecdotes drove fervent pilgrims to different locations. The Benedictine monastic complex, The Abbey of St Mary of the Valley of Jehoshahat, was built by the Crusaders on a site destroyed and rebuilt many times and revered by many as her place of burial, albeit an always empty tomb. Another tradition {ed. Perhaps based on a 4th Century legend that Mary followed John to the present-day Turkish site) offered Ephesus as the final resting place of the Mother of God. To date, pilgrims continue to flock to these sites despite the lack of clear historical evidence. Marian relics began to appear in various places, reflecting the intensifying desire for objects to revere. In the 5th Century, the robe of Mary was brought from Jerusalem to Constantinople to her temple at Blachernae. This relic was accompanied by a painting from St Luke the Evangelist, who is purported to have painted pictures of the Blessed Virgin Mary and Child from the living model, in particular the now-renowned iconic image of the Hodegetria.

In the West, relics of Mary’s clothing began to appear as well initiating a steady growth in shrines dedicated to the Mother of God. In the Middle Ages the cathedral in Aachen, Germany was known as the Royal Church of St Mary at Aachen and the Shrine of St Mary, located in the choir, housed various relics from the Holy Land, among which it was believed, the cloak Mary wore the night she gave birth to Jesus.

The Chapel of the Girdle in the Prato Cathedral was consecrated to honor the Virgin’s relic which was brought back from Jerusalem in 1141 by a Crusader merchant. Other places enshrined similar Marian relics, including a tunic dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary at Le Puy in France. The belief that this relic bestowed fertility to the faithful led Anne of Austria, barren after 22 years of marriage to Louis XIII, King of France, to have it brought to her bedroom. In 1638, she conceived a son, Louis XIV, further enriching the alleged fecund power of the relic.

For devotees of Mary, her childhood home in Nazareth is deemed a treasured and venerated relic. Legend has it that in May 1291, the Holy House of Nazareth was transported by angels across the Mediterranean Sea to Loreto in Italy. Many miracles have been attributed to the Virgin Mary and it is one of the most famous Marian shrines in Italy. In 1920, Pope Benedict XV declared Our Lady of Loreto the patron saint of pilots, airmen and flight attendants.

Speculation surrounding the birth and the death of the Mother of God

Although the veneration of Mary had its early roots in the East, the development of devotion to the Mother of God found fertile soil in the West. This led to increased speculation and investigation into the early life of Mary as well as further research into the circumstances surrounding her death. It was unimaginable to devotees that the Mother of God would, like other mortal beings, have been tainted with original sin. The Dominican friar and scholar Thomas of Aquinas (1225‑1274) contended that the Blessed Virgin Mary, by the grace of God, was free of the stain of original sin from the moment of her birth. The Franciscan theologian John Duns Scotus (1265 ‑1308) asserted that God preserved Mary at the moment of her conception in her mother’s womb from original sin. It was Pope Pius 1X who put an end to the discussion in 1854 when he promulgated the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, “We declare, pronounce and define that the doctrine which holds that the Blessed Virgin Mary, at the first instant of her conception, by a singular privilege and grace of the Omnipotent God, in virtue of the merits of Jesus Christ, the Savior of mankind, was preserved immaculate from all stain of original sin, has been revealed by God, and therefore should firmly and constantly be believed by all the faithful….”

There were varying theories about the end of the life of the Mother of God as well. Since the 5th Century in Eastern Christianity, Mary’s dormition, or literally ‘falling asleep’ was celebrated on August 15th. This Byzantine feast day was celebrated also in the West from the 7th Century onwards. The details of the end of her life differed however. In Eastern icons, Christ was represented as bringing the soul of Mary to heaven whereas in the West, her body as well as her soul were born on high by angels. The portal in the western façade of the Cathedral in Laon (circa 1200), illustrates what theologians will affirm around 1200 and what Pope Pius XII will formally proclaim as the dogma of Mary’s assumption, body and soul, into heaven. The Pope quoted John of Damascus, a Syrian monk and scholar, who said: ‘Her body, which did not lose virginity at the birth of the child, had to be preserved after death in incorruptibility’.

After her assumption, Mary was crowned with many titles, among them the honorific ‘Queen’; Queen of Angels, Queen of Saints, Queen of peace, etc. Gothic cathedrals throughout the Middle Ages sang her praises in stone statues and portals. Although the bible made no mention of her crowning, the scriptures proclaimed her status for all to read. In Psalm 45.10, ‘…upon my right hand did stand the queen in gold…’ In the Song of Solomon or Canticles (4:8) in the Latin Vulgate translation, ‘… come from Lebanon, my bride, and you will be crowned…’ Consistent with these two texts, we see many images of Mary sitting to the right of Christ and crowned by him or by angels.

Eastern Representations of Mary in the West

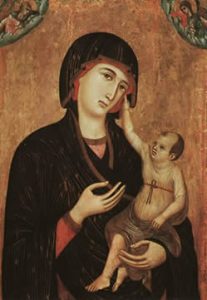

As with Marian veneration and the feast days which were adopted in the West, representations of Mary reflected the Eastern Byzantine influence. In the beginning, the image of the frontally enthroned Maria with her son also in a frontal position was drawn from Eastern iconology. (Ill. 1)

Changes in the depiction of Mary began to be seen in the 13th Century. The hint of a smile on her face began to appear and the child was portrayed as gazing up at her. The infant’s traditional tunic and mantle, symbolizing his wisdom and judgment, were replaced by commonplace children’s clothing. In the same manner, the baby Jesus was shown to be grasping Mary’s veil replacing his customary gesture denoting speech. With these developments, Mary and Christ evolved from a theological concept to an image of mother and son.

Other well-established Byzantine iconic images were embraced in the West, they had a profound influence on Western art, where they took on a life of their own: the Hodegetria,one of the earliest depictions of Mary, and the Eleousa or Virgin of Compassion, from the Greek word for tenderness or showing mercy. Also the Blachernitissa, the orant or praying Madonna, was taken over in the West. The original icon was traditionally associated with the Blachernae Monastery in Constantinople and stood above the shrine containing a mantle relic of the Virgin Mary; a visual manifestation of the garment.

The mantle motif can also be seen in the practice of placing a ‘real’ mantle or cloak over a statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The Netherlands has two well-known Madonna’s that reflect this tradition, de Zoete Lieve Vrouw in Den Bosch and Sterre der Zee in Maastricht. Also in this same vein are the so called rudimentary ‘stake’ Madonna’s whereby the statue has no real body to speak of, but is composed of a head and stick which protrude out of the cloak, the essential part of the figure.

In 1251, Simon Stock, Father General or Prior of the Carmelite Order, received a cloak-like scapular from the Blessed Virgin Mary, who told him, “Whosoever dies wearing this shall not suffer eternal fire, rather he shall be saved.” The scapular, a narrow piece of cloth that hung over the shoulders evenly, front and back, was an existing part of the habit of the Carmelite Order. The brown scapular became a ‘sacramental’ of the Catholic Church; thus extending the protection of one’s soul to all devotees. In the 16th Century the scapular was reduced to two pieces of brown fabric with the images of Mary and Christ, joined together by string or cord and worn over the shoulders. To wear the scapular was to participate in a special relationship with the Our Lady and during the First World War, the Vatican gave special permission for medals to be used in place of the cloth scapulars.

Western Images of Our Lady

In addition to the aforementioned representations harking back to Byzantine, the West developed over time, its own imagery. A well-known example is the depiction of Mary, crowned queen in heaven. In the Middle Ages, Marian antiphons or hymns were created in Latin to honor her position as queen; the Salve Regina also known as Hail Holy Queen, Ave Regina Caelorum and Regina Coeli, both referring to her as Queen of Heaven. These were sung or recited at different seasons in the Christian liturgical calendar. In this same period, there were images to reflect her status; Mary as mother and queen with the infant Jesus. A crown graced her head and she held a scepter in her hand. This image may have found its origins in the real world of the Franks, the newly-created monarchy of the Merovingians established by King Clovis (481 511). In AD 500 he converted to Christianity and status was granted to certain highly-placed females, specifically the queen who had the King’s ear.

Our Lady was accorded many representations; queen, virgin, mother and as a humble, obedient servant of God. This reflects the medieval notions of gender and the conventional conduct for women in this period as virtuous, pure, submissive and domestic. The archetype for this image could be found in the Le Ménagier de Paris(1392-94), a French book outlining the proper behavior in marriage and instructions in domestic management. It was written by a fictional rich, older husband to his child-bride, the central theme being obedience, humility and domestic servitude. Merchant’s wives in the Middle Ages had limited freedom and options, confined mainly to the home and the duties of running the household. This medieval theme of the virtue of humility can be seen in the various representations of the Madonna dell’Umiltà or Madonna of Humility found on altarpieces, murals, frescos and paintings. This code of humility and obedience extended to the monastic orders as well. These 14th- Century images of Mary depicted her not on a throne but either on the ground or a cushion, further signifying her humble connection to humus or earth and her submissiveness.

Objects of Devotion

Although churches were and are the primary centers of worship, veneration to God was not confined to them. Monks and nuns meditated and prayed within the confines of their cells and devotees prayed in the privacy of their homes. To accommodate this growing market, small statues and paintings, illustrated prayer books, devotional objects in many forms were created as early as the 15th Century. In the Netherlands small religious statues made in molds from a fine, white clay were mass-produced in many places, especially Utrecht; an affordable alternative to the more expensive wood statues. Many Catholic families in the 19th and 20th Centuries purchased bulk-produced plaster statues of Christ, Mary and the saints.

The Immaculate Conception

Another representation of Mary in the West was of the Immaculate Conception. After the council of Trent, the classical image of the Immaculate Conception emerged. At the base of this image are the words of Genesis 3:15, (Vulgate translation): “I will put enmities between thee and the woman, and thy seed and her seed: she shall crush thy head, and thou shalt lie in wait for her heel, “words spoken by God to the serpent after the Fall of Adam and Eve. The image of Mary with her foot atop a serpent, was connected with the vision of the Woman of the Apocalypse (Revelations – Apocalypse 12.1): a woman appears in heaven ‘’clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, wearing a crown of 12 stars’’.

In 1856, four years after declaration of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, an apparition in Lourdes appeared to bear this out. A young woman in a white gown and a blue waistband appeared to Bernadette Soubirous announcing herself to be the Immaculate Conception and requesting that a chapel be built on the site. Blessed Virgin Mary apparitions occurred also in the 20th Century at Fatima, Portugal (1917), Beauraing (1932-1933), Banneux (1933), both in Belgium and in Amsterdam (1945-1959) introducing the new designation of Vrouwe van alle Volkeren, or The Lady of All Nations.

Conclusion

The anonymous woman spoken of by St Paul in his Epistle to the Galatians (4:4) has through history evolved into a figure of phenomenal proportions. Seen as a contrast to Eve, Mary is also equated with the woman who appeared as ‘a great sign’ in the heavens. (Revelations – Apocalypse 12.1). She encompasses a multitude of representations: crowned in the heavens seemingly distant yet giving comfort and help to all who beseech her, as if she was very near. Freed from Original Sin and the pains of giving birth (in stark contrast to Eve; ‘I will multiply they sorrows and thy conceptions; in sorrow shalt thou bring forth children…’ Genesis 3, 16), Mary remains a virgin for all time. Nonetheless she is loving mother and dutiful bride. Despite the fact that she is mentioned only sporadically in the Apostolic Letters or Epistles and just one time by name in the Acts of the Apostles (1, 14), ‘…with one mind in prayer with the women, and Mary the mother of Jesus…’, subsequent theologians make reference to her even before her birth and after her death. They speak of her conception in purity in the womb of Anne, her mother and of her crowning as Queen of Heaven.

In the many effigies of Mary, she is a simple, naïve girl, a cotented or distressed mother as well as an elderly woman whose face reflects the suffering she has endured. She is portrayed with her infant son Jesus in her arms and cradling the battered body of the crucified man. Mary is a theological idea that speaks to the minds of many and a figure that touches us deeply when we see her lovingly depicted with the baby Jesus or exposing her grief as Mater Dolorosa standing under the cross. The countless words spoken about her in pious supposition, reverent speculation, in religious and theological study are reflected in the scores of images and representations of the Virgin Mary found in the great churches and museums of the world and the small devotional objects holding pride of place in the homes and hearts of her devotees.

By dr. Peter van Dael

Translated by Lorraine Weber